Sitting Under The Plastic Tree

A popular West Africa travel guide describes the dark side of its industry: “Tourists create tremendous amounts of rubbish, particularly non-biodegradable packaging such as plastic bags and water bottles.” This, it continues, is a serious problem in areas where traditionally all trash decomposed naturally.

While there’s truth in this observation, it ignores several realities that make the environmental picture in West Africa much more complicated.

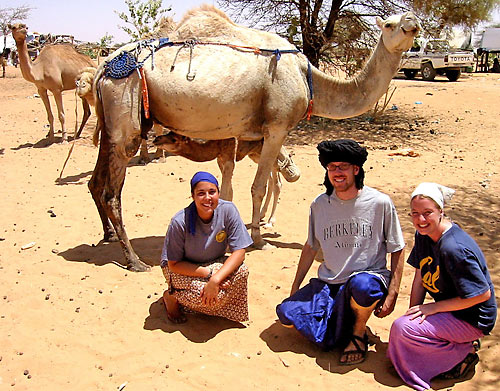

Let’s travel through Mauritania from city to town to village and see what the realities are, using my province, the Assaba, as an example. In Kiffa, a city of 50,000 with close to zero tourism, nearly every product purchased and consumed is made of or packaged in non-biodegradable materials. Combine this with desert winds and a lack of trash collection and you’ll understand why I commented in my first week that, “it seems the plastic bag tree grows very well in this country.”

From Kiffa travel 85 kilometers south through dirt and sand to Kankossa, a town of around 5,000 people. The local economy is still heavily influenced by plastic, because even without an improved road, 50-75% of the goods available in Kiffa make their way here, albeit at higher prices. Head seven kilometers southwest and you’ll reach Agmamine, a village with a population of around 1000. Because there is almost no commerce, you see few water bottles strewn about, and almost no plastic bag trees. But villagers still need buckets to bathe and wash clothes and haul water out of the well and to their door, and surprise surprise, these are the same plastic products sold in Kankossa. In this sense, Africa’s “traditional villages” are growing scarce indeed, but not thanks to tourism.

Think about it: lightweight, strong, rot and rust proof, easy to clean, and cheap. That’s why developing country businesses and consumers, with low levels of investment and income, love plastic. It scores high in a cost-benefit analysis, unlike many western-pushed development efforts, which tend to score low and thus fail no matter how hard the push.

I turn my head 180 degrees on my porch and spot the plastic items that nearly all other Mauritanian families have: buckets, bags and baggies of all sizes, floor mats, bottles, cups, shoes. And here’s a factoid that makes the already tired Globalization Kills argument even more trite: most plastic products sold in Mauritania are made in Senegal. Those evil Americans, I mean Europeans, I mean foreigners, I mean…West Africans? They must get foreign investment, the conspiracy theorist might comfortably imagine.

On a recent trip to Dakar I saw a ray of hope for the very real problem of plastic bag trees when I visited a nascent recycling business founded with the assistance of EnterpriseWorks/VITA, a US-based NGO (also my former employer). This company collects plastic waste like bags and sandals, chops it up using everything from machines to an old man with a machete, and sells it back to Dakar’s plastic manufacturers as pellets. With good management, good marketing, and good luck, this will become a profitable business, and plastic producers will as a matter of course churn out new products with a percentage of recycled material. Not because they’re environmentalists, but because it’s good business.

So here’s my two cents on the global energy and sanitation situation. Extracting petroleum from rock or ocean governed by myopic thugs will never foster political stability, civil society or economic development for all. Let’s take all the bright minds we can spare and make alternative energy more economical. Let’s work on market-based recycling. Let’s fight corruption and push for governments that collect more trash and buy fewer cars. And let’s encourage tourists to leave a small footprint.

But don’t cry out that plastic is destroying Africa. The alternatives – making everyday products out of wood or metal or not having them at all – could be just as bad or even more destructive.

<< Home