Applied Freakenomics

In Freakenomics, Stephen Levitt’s much-hyped new book explaining social science phenomena in terms of economics, the author makes a provocative statement about parenting. Imagine your child plays regularly at the houses of two friends. One house has a swimming pool. The other has a gun. Your child is safer at the house with the gun by a factor of 100.

More than 500 children under the age of 10 drown in swimming pools every year in the United States. One of them lived across the street from my aunt and uncle Agnes and Bill in Franklin Square, New York. It’s always the same tragic story, with a baby/toddler/youngster slipping into the backyard while the caretaker is distracted. Five minutes later, a family is destroyed.

Upon my return to Kiffa in July, I walked down the rocky hillside from my house to the fast food restaurant run by a hard-working man named Boubacar. His quick and cheap sandwiches have kept me going over the last year, and what’s more, he is a friend. Boubacar taught me about Mauritania, the restaurant business, and life in general. He managed the business for someone else and was dying to strike out on his own.

Boubacar rarely took a day off, so I was surprised to see the restaurant shuttered on a weeknight. I got the story from another regular the next day.

It turns out that his son Sidi drowned while I was on vacation. Mauritania has very few swimming pools, but concrete reservoirs and tanks are everywhere, storing water for drinking, irrigation, or commercial activities. The back of the restaurant opened up onto a brick making enterprise, and Sidi must have somehow drowned in the concrete reservoir. The family packed up and left Kiffa without a trace.

Sidi was six years old, and he and his five-year-old sister Aisha were an adorable pair. Sidi was the lapdog, wanting to please his father, and Aisha made enough mischief for them both. As Boubacar observed, when he disciplined Aisha, her big brother cried. When he disciplined Sidi, his little sister laughed.

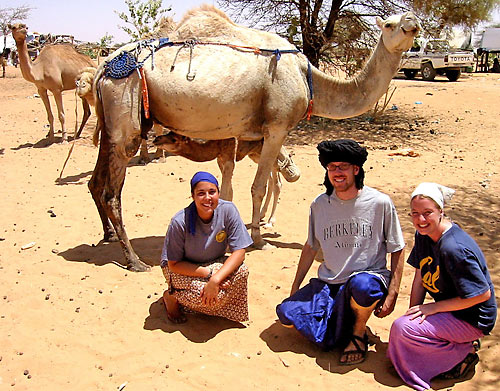

I returned to Kiffa with new ideas for Boubacar – how to get a line of credit sufficient to start his own restaurant – and with photos – one of me wearing the purple wax print boubou he gave me, and another photo of his family. It’s a grainy night-time shot, with the flash lighting up the dust and sand in the air. But the scene is clear enough – a family captured in time, just before a catastrophe. Boubacar looking proud, his wife Kumba smiling bashfully, and their two children. Aisha the troublemaker. Sidi the quiet kid who one time rescued a kitten and raised it with food scraps and condensed milk.

I will try to find Boubacar in Nouakchott, but with probably 20,000 Boubacar’s and no leads, it won’t be easy. If I do find him, I have the photos, and a few phrases of condolences from my Hassaniya book, which hinge on an idea that’s also familiar in much of America: trust in God, he has the master plan for our lives.

Reading Freakenomics from Mauritania has taught me that not all statistics are the same, and that they’re useless by themselves. The Western world’s obsession with data may be neurotic but it has benefits – every death is labeled, categorized, and pushed through regression analysis. Products are made safer. People are made aware. In the developing world, people fall into wells, get thrown from cars, die of preventable diseases, and are largely forgotten. At best, the information is fed to under-funded governments or development agencies that attack problems as best they can.

<< Home