The Village Life and The Gimme Economy

=== The Village Life ===

Halfway into the ten kilometer walk to Agmamine – a village of a hundred or so families west of Kankossa – I thought my backpack was leaking. What else could explain the water streaming down my back, soaking my pants and shirt? Caleb took a peek. “It’s just sweat, don’t worry,” he said easily. The guy actually seemed to be enjoying the walk, while my aching back was about to start with the “are we there yets?”

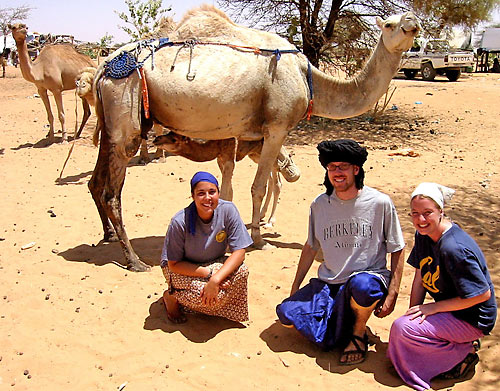

Andrew and I joined Caleb for two days at his site, a beautiful village of thatched and mud huts resting on a sand dune next to Lake Kankossa. We departed Kankossa at 4:30 in the afternoon, with the aim of arriving just as the sun sets and families break their Ramadan fast. After a couple of short stops for water and photos (the walk is just trees, animals, and a dirt track road, like a desert nature preserve) we came upon Agmamine’s first houses as the sun disappeared beyond the lake, the call to prayer rang out, and families lit their cooking fires in the dimming light. Our backpacks fell heavily onto the dirt floor of Caleb’s house and we greedily broke fast with milk and dates. And we weren’t even fasting!

Coming from Kiffa, a city of 50,000 people with mostly gridded streets and walled compounds, there’s something incredible about descending onto a village of people living together with no fences, walls, or other distinction between what’s mine and yours. We slept a hundred feet from 50 head of cattle, and my only complain is it can be difficult to sleep through the night in Agmamine. There’s something about a donkey’s cry to give the illusion that it’s in great pain and is holding you responsible.

As an agro/forestry volunteer, Caleb has a number of projects in the works, including his own demonstration garden (about 200 times the size of my little plot). A 25 square meter garden demands a lot of fertilizer, so the three of us spent some time shoveling and transporting manure to his compost pile. We loaded up the wheelbarrow with fresh cow pies, and with one person pushing and two pulling with string we trudged through the sand to Caleb’s garden. We worked early morning and late afternoon and rewarded ourselves often – slightly chunky, sour milk (a bit like a yogurt drink) and fresh milk being my two favorite treats.

I still laugh at the fact that with all the cows in Agmamine, Caleb’s biggest culinary nemesis happens to be milk. He’s also not too jazzed about the local food, so after Andrew and I polished off our plates and bowls of milk, he said “thanks guys. Now they’re going to know that some white people DO eat and drink a lot.”

=== Humor Remembered ===

Early on the first day of Kiffa’s polio vaccination campaign, the man and woman on my team began walking in separate directions. “Ane lahi nbull” Hasan said. I said “definitely” and followed him, not thinking about what he said but assuming I should follow the man. When he saw I was following him, he stopped and said it again. “Ane lahi nbull.” I looked at Merriam. She said it a third time. Ohhhh, he’s going to go PEE. I’ll go with you, then, I said to her, trying not to look too embarrassed. Quick Hassaniya lesson: You now know that ibull is the verb “to pee.” Mbulti is “my bladder” and if you really have to go, you can say “mbulti lahi tishreg” which means “my bladder is going to burst.” I’m saving that line for my next long taxi ride.

=== The ‘Gimme’ Economy ===

Warning, I’m going to become momentarily philosophical. One of the most impressive aspects of the work of my last NGO (EnterpriseWorks) is that they don’t give things away. Period. From what I’ve seen about the NGO activity in Mauritania, it’s Handout Central. I’m still learning about how these organizations work, and I’m sure they do good work, but there’s something awry when a seemingly wealthy rural Mauritanian (has a large herd of cattle and owns a boutique) wants to enclose his garden and is waiting for a local NGO to donate fencing.

It makes sense for him – who wouldn’t try to get it for free? – but what effect does this type of activity have on economic development? In essence, NGOs and donor funded projects have become a permanent addition to the supply chain in almost every economic sector, all across the developing world. NGOs raise money, through development banks (say, the World Bank), bi-laterals (like USAID) and (World Vision or Lutheran World Relief, for instance) from generous individuals all around the world hoping to do some good.

The contortion of good intentions, whether its fencing given away to a farmer who could have afforded to buy it, or donated food and clothing that’s resold in the markets, doesn’t appear to hurt anyone in the short term. Joe gets a tax write off in Chicago, Mohammad the NGO agent makes his friend happy, and Brahim has a new fence to keep out the goats. But in my ever changing and admittedly ‘newbie’ opinion, the Handout Economy doesn’t only ignore sustainable development. It prevents it. And to think I haven’t even read Ayn Rand yet!

=== Book Review ===

Hard-boiled Wonderland and the End of the World

By Haruki Murakami

It’s possible that Haruki Murakami is already amongst the world’s best novelists. Or at least, that’s what it says on the back of his 1985 novel about unicorns, data encryption, and split consciousness. But in all seriousness, Murakami is a master of modern day surrealism, and while “Hard-boiled” is one of his early books (A Wild Sheep Chase takes some of his techniques and brings them forward with more sophistication), it sings from beginning to end. Even the title, don’t you want to say it again and again?

Like most of Murakami’s work, “Hard-boiled” takes place in Japan and brings in gangster elements that aim to swallow up a down-and-out but generally likable business man. In this case, the protagonist (none of the characters are given names) seems like your average techie, but actually he mentally encrypts and decrypts sensitive data for the government using cutting edge equipment implanted via a procedure that burrows straight into his “core consciousness.” He realizes that he’s in the middle of a crisis that could end the world as he knows it when he comes home from a job one day and realizes that he’s been given a unicorn skull that some bad guys want to steal.

I know what you’re thinking, it sounds like science fiction, and there is a certain Blade Runner (or “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” to be more exact) quality to the book, but Murakami writes beautifully with delicate metaphors at every turn. For instance, a character doesn’t just fall asleep, sleep washes over him or casts a net over him, and he doesn’t just hurt from a wound, he waits at the crossing for a boxcar of pain to pass. And though his characters are anonymous, they come to life, like the 17 year-old chubby home-schooled girl genious who wears pink everything and makes surprisingly delicious sandwiches while he crunches numbers on a job.

There’s a great interview on Salon (Google search Murakami and Salon) that gives more information about the guy – he clearly has a love-hate relationship with Japan as he writes about his homeland but lives in the U.S. And he constantly drops in the names of western songs, movies, and books, for example his novel “Norwegian Wood.” Or maybe that’s just globalization talking. If anyone has any more Murakami lying around, I would be happy to write more reviews. Hint, hint!