Foxhole Cooking

For the first time in the history of foreign assistance, an international relief and development organization has issued a famine alert for its own employees. Due to poor grain harvests and dwindling livestock counts, Peace Corps volunteers in the African Sahel are dropping at an alarming rate. Size 12’s are wearing 4’s, and pants lacking drawstrings are now adorning scarecrows in vegetable patches.

The United States Government has responded to this emergency with typical generosity and efficiency. Until further notice, PCVs can request Meals Ready-To-Eat (MREs) from their medical office.

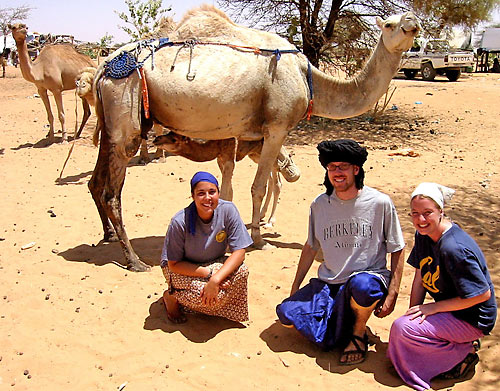

As a city volunteer, I generally get enough to eat and suffer only from monotony and small portions. In fact, the military rations are probably more closely intended for two married volunteers on the edge of the Sahara, who subsist on boiled grains, occasional meat, and their imaginations. We’re talking about two narrow individuals before Peace Corps, but now I’d estimate they weigh a combined 135 pounds.

So it wasn’t without a tinge of guilt that I sucked in my stomach and limped into the medical office complaining of blurred vision and a diet of boiled cardboard. I limped out with high-calorie, vitamin enriched, and surprisingly tasty proof that women play an important role in military policy and planning.

The days of You-Know-What On A Shingle are over. My entrée options include Vegetarian Fettuccini Alfredo, Beef Teriyaki, and Chicken Strips with Chunky Salsa. You can start off with jalepeño cheese spread on a vegetable cracker, or maybe some spiced apples. And for dessert, why not enjoy a cup of coffee and lemon pound cake?

The best part is there’s no stove required, thanks to the smartly named OPN63 NSN 8970-01-321-9153 heating unit. Just plop the main course into this plastic sack with a chemical wafer at the bottom, add water, and in 10 minutes it’s ready. They even throw in a kind piece of advice: “the contents will be HOT.”

I can’t find an expiration date anywhere on the packaging, but judging from the serial numbers on the rancid Snickers bars, I’m guessing our batch is from 1998. But the shelf-life is impressive, as the parts of the MRE are zipped up separately in high-tech shrink wrapping by DOD contractors like Sopakco Packaging, Mullins, South Carolina. I imagine the corporate tagline “You make it, we’re fixin’ to pack it.”

Each meal comes with an accessory packet containing plastic spoon, napkin/TP, wet wipe, tiny bottle of Tobasco sauce (I imagine tiny Mexican women squeezing tiny red peppers), matches, and beverage powder, everything it seems except for a temporary tattoo or hologram toy.

As if this all wasn’t quite enough, the boxes are stamped with nutrition information written in unmistakable Pentagon-speak. “Fortification Provides you the Additional Edge to Maximize Your Performance.” I suppose, but after the beef stew and brownie, the last thing I’d want to hear is “MOVE OUT, MEN.” I require a nap, sir.

From one perspective, MRE’s are a desperate last resort to starvation, and my level of enjoyment stems mostly from the memories of American food evoked in the face of monotonous desert fare. But still I’d say that MRE’s are so ingenious and fun, it’s only the low pay, physical requirements, and dislike of raised voices that’s keeping me from enlisting right now.

Until then, I’ll assume the diet and attitude of a 21st Century Yossarian with a billet that’s decidedly more Rear Echelon.