You Don't Remember Your Name

Halfway between Kiffa and Nouakchott with Mike Dubrall and his daughter Annika (Kankossa), I brought up that old America song about the desert and the horse and not remembering your name. “I think that song was about drugs,” Mike replied. Was Annika blushing or sunburned? We changed the subject.

That may well be, but I just returned from a camel trek in the north of Mauritania, and without any drugs or alcohol our guides were unable to remember the names of two of the four members of our group. And they have THE SAME NAME! Just a bit eerie, perhaps?

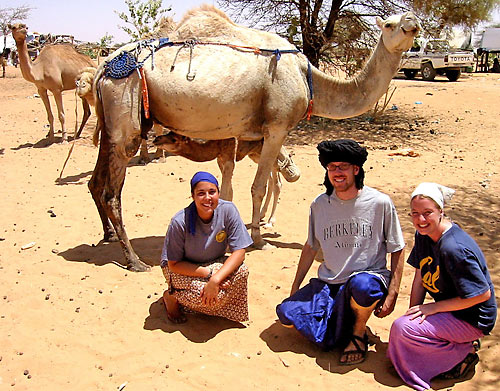

Last summer fellow PCV Keith (Atar) began to develop plans for a camel trek that would live or die in infamy. The trip covered six days and 100 kilometers, starting at the oasis of Tergit and ending up in Chinguetti, Islam’s 7th holiest city. Jarad (Aioun) and Jared (Kobeni) and I made our way to Atar and met Keith, departing for Tergit with our backpacks and two boxes of military rations (see story in next issue “Foxhole Cooking”).

Our goals for the trip were unspoken, but understood. Have a good time. No whining. Don’t fall off. Try not to kill each other.

So did we succeed? Mostly. But I can’t fairly describe the experience in a chronological account. Instead I offer two equally true interpretations of one day.

-

Day three. We woke with the sun, ate flatbread baked in the sand under hot coals, and left our campsite around eight o’clock. Walking just ahead of the camels, we ascended a gentle grade covered in jagged boulders and slices of sun-varnished slate, where spiny black lizards took cover from the already searing sun. We reached the summit and drank in the view – an ocean of dunes interrupted a few kilometers beyond by a menacing rock face.

Our young but knowledgeable guide Saleck led us down the hill and through the valley of sand. Each successive dune passed like the face of a wave. Lashes of hot wind whipped across the marbled sand, dotted with the tracks of beetles, snakes, and camels.

After lunch we ascended the small mountain to get a view of the route covered that day. As our thighs burned from the climb we named it Mt. Misery. At the peak we explored caves dotted with animal droppings, nothing large and hungry we hoped. After descending and collecting our belongings from the woman’s house, we continued our journey until finding a well at sunset and setting up camp for the night. Exhaustion prevailed, but a sense of accomplishment was close behind. We had reached the halfway point.

-From Hunter S. Thompson’s Private Collection-

“They made a G.I. Joe doll out of that guy?” I asked, effortlessly flipping my machete into the air. “It was called The Fridge G.I. Joe,” Keith repeated for the fifth time as Jarad lit military rations aflame, sending plastic fumes into our excrement filled cave on the top of a rocky hill in the hellish Sahara. An image of William “The Refrigerator” Perry celebrating a touchdown surfaced in my brain and was quickly replaced by a Victoria’s Secret model made out of ice cubes. “We’ll call this place Mount Fridge G.I. Joe,” suggested my personal assistant Zanzibar, the three foot tall Malagasy healer we found on day 41 half-buried in sand. The name stuck and we ran down the sandy rear face of Mt. Fridge G.I. Joe as our bare feet melted in molten lava and Jarad screamed “GET TO THE CHOPPER!!!!” Keith thought he actually was Arnold Schwarzenegger from “Commando” and began to cry under a thorny tree. I comforted him by singing “Careless Whisper” and promised that he could ride Jugenjebu our German camel after lunch.

We returned to the home of the overbearing woman who tried to sell us expensive junk, propose marriage to anyone who would listen, and brag about her head lice. And that’s when we realized that Jared had been transformed into a Billy goat and was being chased by Whitaker our British camel. Back on the endless route to wherever we were going, we debated the possibility of time travel in Hassaniya, agreeing that light goes “really really fast.” Jarad brought it all together with a story about his ex-girlfriend in El Paso. “Guilty feet have got no rhythm,” he admitted.

...Both versions are more or less true, you see? The lesson is that a drug and alcohol free excursion in the desert can be even more dangerous than America and Hunter S. Thompson combined. So let’s all say it together: “NEVER AGAIN!”